ME -- LEGAL IMMIGRANT

ME -- LEGAL IMMIGRANTAs they say in Canada, ARE YOU LANDED?

My father was raised in northern Minnesota, and thus had as much awareness as any American might of his northern neighbor, Canada. (right: High Falls of Pigeon River, U.S./Canadian border -- hat-tip Bryan Hansel)

So even in the t

emperate climate of Portland, Oregon, where I grew up, my father’s northern sensibilities were instrumental in cultivating in his kids (female though we were) a passion for ice hockey, honorably fed for over a decade by the Portland Buckaroos. They were Canadians one and all, from such exotic places as Saskatoon and Sault Ste. Marie and T’ronno.

emperate climate of Portland, Oregon, where I grew up, my father’s northern sensibilities were instrumental in cultivating in his kids (female though we were) a passion for ice hockey, honorably fed for over a decade by the Portland Buckaroos. They were Canadians one and all, from such exotic places as Saskatoon and Sault Ste. Marie and T’ronno.As a result we shared even more in the ordinary Pacific Northwesterner’s interest in crossing the border and visiting British Columbia, where we camped and toured several times. We felt every Oregonian’s easy affinity for a country, a landscape, and a people who seemed much like our own—less “foreign” to us, perhaps, than people from Texas or Massachusetts.

That being my experience, it wasn’t a difficult decision to opt for

the University of Victoria, on beautiful Vancouver Island in 1971. During the spring of my senior year there, in 1974, Canada instituted an amnesty plan to regularize the immigration status of various types of residents. The publicity for the program seemed to me to be aimed at American draft dodgers and others with legal problems, so I ignored it and missed the application deadline-- only to discover too late that a lot of foreign students like myself had taken advantage of it to acquire Landed Immigrant status, and the benefits (especially work permits) that went with it.

the University of Victoria, on beautiful Vancouver Island in 1971. During the spring of my senior year there, in 1974, Canada instituted an amnesty plan to regularize the immigration status of various types of residents. The publicity for the program seemed to me to be aimed at American draft dodgers and others with legal problems, so I ignored it and missed the application deadline-- only to discover too late that a lot of foreign students like myself had taken advantage of it to acquire Landed Immigrant status, and the benefits (especially work permits) that went with it.By the time I had decided to stick around after graduation and accept a job offer, Landed Immigrant status had become much more difficult to obtain. I ended up staying in town as a visitor, working for no pay, and leaving the country to undergo an interview at the Canadian consulate in Seattle – [“Parlez-vous français?” I was asked without warning, mid-conversation—an absurd question to almost any Canadian west of Wa-Wa, Ontario] – and later exiting once again to, enter properly when my papers finally came through.

I planned to stay for a few years before returning Stateside— even bought a one-way airline ticket back home once, which I ended up selling to someone else. But in 1980 I married a Canadian and have lived here ever since. Nationality was not a particularly big deal in my mind when I went north the first time, and I was fairly indifferent to the idea of becoming a Canadian citizen. I have periodically flirted with it over the years, especially back when I still thought it might be nifty to promise allegiance to the Queen. But between the ongoing follies of Her Majesty’s pathetic offspring, and the picture of increasingly unchecked anti-Americanism among many Canadians, especially those in high government office, I have never been less interested in signing on to the electoral rolls than I am at this present moment.

I have great Canadian friends, and a small, close community I would be reluctant to part from. I’ve always cheered for Canadian Olympians (and for their Olympic TV coverage, which is consistently superior to the smarmy American stuff). NHL hockey’s not what it used to be, but I’ve been to the Gardens and Forum, and still watch the play-offs (LEAFS SUCK – GO HABS). I am never reluctant to sing the National Anthem in both official languages—been doing that since I was about 8. Still, I’m an alien in a foreign land. And although now having a Canadian husband and children probably protects me from certain punitive measures, I have never believed that, were I to run afoul of Canadian law, I should be above deportation to my country of citizenship.

When the joints were being passed around at the university house parties, I would have fully expected to get the boot if we got busted. (As if anybody would care! It was B.C.!) I’ve attended a demonstration or two in my time—had I ever been detained for any reason, I would understand if my residential status were to affect the legal consequences of my actions. If I failed to pay my taxes or to declare my purchases at the border, if I scammed old ladies out of their pensions and the government out of its benefits, should Canada choose to draw a distinction between the penalties for citizens and those for foreigners like me, that has always seemed reasonable to me. I’m not a Canadian citizen, nor likely to be.

As it happens, in the past 40 years Canada has modeled itself so closely on continental Europe that its own indifference to citizenship concerns leaves me and my fellow Landed Immigrants pretty safe. It’s hard to imagine what anyone would have to do to actually get deported from here. (Deportation orders do get issued, but enforcement is ridiculously lax.) Yet I have never taken for granted any right to be treated like those who have signed on for Queen and country. I’ve made a conscious choice not to, and my status is no more than what it is. On the other hand, I did stand in line, and went to the trouble of obtaining that status properly, legally. This does accord me a certain prescribed set of rights and privileges.

That’s a status I share with the people who came before m

e: my Irish ancestors who entered the United States (some via Canada) in the 1850’s, as did the Bavarian farmers of Minnesota, or my Greek grandfather whose name is on the Immigrant Wall of Honor on Ellis Island, where he entered, a boy of ten all alone, in about 1905. I entered Canada on a well-maintained, gleaming white car ferry that do

e: my Irish ancestors who entered the United States (some via Canada) in the 1850’s, as did the Bavarian farmers of Minnesota, or my Greek grandfather whose name is on the Immigrant Wall of Honor on Ellis Island, where he entered, a boy of ten all alone, in about 1905. I entered Canada on a well-maintained, gleaming white car ferry that do cks in the downtown harbor in front of the old-world-glamorous chateau-style Empress Hotel, amid banks of flowers and shops peddling tea and tartans. I didn't share my ancestors' experience of stinking steerage and sea-sickness and button-hooks under the eye-lids. But we all waited our turn, and jumped through the hoops required of us.

cks in the downtown harbor in front of the old-world-glamorous chateau-style Empress Hotel, amid banks of flowers and shops peddling tea and tartans. I didn't share my ancestors' experience of stinking steerage and sea-sickness and button-hooks under the eye-lids. But we all waited our turn, and jumped through the hoops required of us.I have always thought Canada's official bilingualism was the stuff of a foolish delusion, but they tested my French before admitting me, and that was their right. Should I ever seek citizenship, it will be expected that I'll have a grasp of Canadian history and be able to sing the anthem (no sweat on either scale), and if my 32 years of residence without citizenship were to give anyone pause, that's their right too. Love of an adopted country is important, but it is first and best expressed in respect for its laws, and humility in the face of its gracious welcome.

The spectacle of thousands of Mexican flags waving above bullying avowals that "Tomorrow We Vote" told a tale that could not be obscured by mist of sympathetic reportage. People who have worked hard, paid taxes, and kept out of trouble have not done the United States a kindness, nor have they "earned" a reward-- they have exploited the country's administrative incompetence for their own self-interest. Not a mortal sin -- maybe -- but not, by any stretch, a virtue.

It's a situation that must be dealt with, with justice (which may not be easy to define) but without guilt-laden hand-wringing and bathos. We used to be made of stronger stuff than that-- and we looked to our immigrants to follow our lead.

ONWARD!

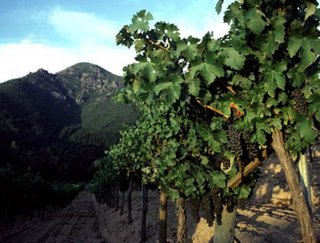

Why don't we start by checking to see if the guys picking grapes in

Nancy Pelosi's non-union California vineyards have any genuine ID.