September 13, 2001

Please contact me at ***@hotmail.com if you have any knowledge of the whereabouts of my husband, Jack Aron, who works for Marsh and was on the 95th floor of 1 WTC. My 11 year old son & I love him dearly and are so worried. Please let us all pray for him and all the other victims.September 14, 2001

[St. Petersburg Times – Electronic cries of desperation]

Marsh USASeptember 19, 2001

Status: Of the 1700 employees who worked at the WTC and the 50 to 100 visitors scheduled to be there Tuesday, 1400 are safe as of Sept 14th.

[www.WorldTradeAftermath.com – company contacts page]

September 20, 2001MISSING: Jack Aron

Jack Aron, 52, of New Jersey, worked for Marsh & McLennan on the 95th floor of Tower One. His family includes a wife and one child. He is described as five-seven and 140 pounds, of Caucasian descent with black hair, dark brown eyes, and a mustache. He is wearing a gold wedding band.

[Village Voice – For Whom the Bell Tolls, Part II]

Nine days after the most devastating terrorist attack against the United States in history, the known death toll of victims continues to rise. New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani said there are 233 confirmed fatalities, and 170 have been identified. Those identified included 37 policemen, 35 firefighters and two emergency medical technicians. He said the number of people missing is 5,422.November 9, 2001

[list of fatalities does not include Jack Charles Aron]

[FOX NEWS -- Terrorist Attack Victims]

By the latest official count, 600 people are now confirmed dead at the World Trade Center. 3,770 remain missing. Including the Pentagon attack and the United Airlines flight that crashed in Pennsylvania, the dead and missing number 4,603.+ + + + +

PBS -- The News Hour with Jim Lehrer]

Jack Charles Aron, 52, Bergenfield, N.J., information technology, Marsh & McLennan Cos. Inc. confirmed dead, World Trade Center, in or at building.+ + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + + +

[www.september11victims.com]

I had forgotten.

I thought I would never forget a thing about that day. But in the years that have followed— through grief and anger and pride and fear; through shock and awe, through aggression and paralysis; through “jaw-jaw” and “war-war” (as Churchill understood them); through memorials and monuments, and up and down the endless list of names— I had forgotten that in those first hours and days, growing into weeks, of numbed confusion, the missing were not yet presumed dead. The search had not yet been called off. There was still faith and hope that the nightmare might yet end in joy.

Eventually reality clobbered all of us. It was a reality so mammoth one could hardly imagine ever being able to forget or suppress a particle of it. But the evidence argues the contrary: too many people, throughout many nations, even those who have been victimized by subsequent attacks, have permitted themselves a comfortable amnesia that leaves them carping or sneering or puzzling as to what all the fuss is about. The 2996 Tribute Project has been initiated to remind all who have eyes to see and ears to hear of the precise measure of that terrible day’s loss.

Upon hearing about the 2996 Project, it was my first hope to be able to write a tribute to one of the two victims whose families I have been privileged to meet. I didn’t lose anyone that I knew personally that day. But one of my son’s classmates lost a father. Within a week of the attack I attended the memorial Mass for Ken Basnicki at the school, and within the year I met his family, as well as that of WTC victim David Barkway, at the American Consulate 4th of July gathering in Toronto, held to express the shared grief and to celebrate the long (albeit sometimes abrasive) relationship between our two nations. I figured I would do my best work if I could write about someone whose story I had already been following closely, and with whom I had even a tangential personal connection.

But the 2996 list showed that both those names had al ready been covered. So in registering for the project I was assigned the subject of my tribute essay—a stranger. I was invited to meet Jack Charles Aron.

ready been covered. So in registering for the project I was assigned the subject of my tribute essay—a stranger. I was invited to meet Jack Charles Aron.

These days most everybody knows where you go to find out about a stranger. Punch his name into an internet search engine and his story starts to unfold. Google a September 11 victim and peculiar things can turn up. I found Jack Aron at the somewhat ghoulishly-named “findagrave.com”. A page of Arons listed burial sites like Riverside Cemetery, Arlington National, Holy Family, Odd Fellows, Greenoaks, and Arab Memorial Cemetery. A Private 1st Class Edward Aron has lain in the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in France since 1918. Private Jerome Aron was buried at Luxembourg American Cemetery in 1945. But when you “find a grave” for Jack Charles Aron in 2001, it’s not like the others: his burial place is listed as the World Trade Center.

Most sites turned up in a September 11 name-search are simply lists of all the victims’ names. Countless people feel the need to express themselves about that day, and put all their creativity into sites with complex and impressive graphics. Then they search for words, and for most of them the only words that speak the awful truth are the names. List them single file, build a wall with them, no matter how you set them out, the sheer size of the list— the amount of space taken up by those thousands of words— never fails to take one's breath away.

A more painful variation is to open the way for every one of those listed names to blossom into a story, inviting contributions from anyone who has a memory, a tale, or a good word to say about each individual. What’s wonderful about these “guestbook” websites is that they are obviously visited not just by the circle of friends who mourn the particular victim, but by strangers who stroll by, stop and read, and are moved by what they learn about someone they have never met.

I found four guestbook sites paying tribute to Jack Aron. Between October 2001 and August 2006, thirty among the hundreds of visitors to these sites left messages. One man who worked with Jack in the 1970’s, and had seen him only intermittently since then, left tributes on all four guestbooks over the course of four years. This colleague, Bill, always gave the basic details of their friendship, but he took the trouble to compose something a little bit different for each entry, even the two written on the same day in 2004. It was Bill who could not say often enough that Jack Aron was the mildest, sweetest, gentlest man you could ever meet. He also called Jack a mensch. But, most tellingly, Bill described Jack Aron as “the antithesis of those that caused his death.”

Of the thirty messengers, twelve were Jack’s friends, co-workers, neighbors, and childhood schoolmates. The other eighteen didn’t know him at all. Some shared his hometown; one went to the high school that was his town’s fiercest rival; one Israeli man felt a connection because they shared two names—“Aron” and “Charles”. But most were just moved to comment on the picture, drawn in words as well as images, of an ordinary guy who inspired some extraordinary feelings.

Jack Charles Aron was a physically slight man, as the distress message above describes him (5’7”, 140 lbs.), and as his friends remember him: diminutive, angelic, with beautiful, large brown eyes.

One of the richest qualities of these dozen friends’ memories is that they speak of several different phases in one man’s life. The school friends remember sports teams, dances, first drinks, broken hearts, their generation’s music (Jack introduced them to the Beatles, had the best stereo, sported long hair, and went to Woodstock). One recalled that behind Jack’s dry humor and hip tastes was his deeply troubled childhood as the son of Holocaust survivors—a background he seems to have weathered better than other family members, for some friends remember Jack as an up-and-coming young businessman burdened with the care of his older brother, who had fallen prey to substance abuse.

Co-workers remember Jack Aron as an exacting manager with high standards, and a stickler for detail. But he was equally a fun and friendly presence at his office, and he seems to have left one predominant impression with everyone he worked with at a series of firms: that marriage and fatherhood (which came to him somewhat late in life) were his greatest source of happiness. He talked endlessly of his son Timmy, only 11 when Jack died at age 52. Jack earned his “great dad” designation by coaching his son at baseball and basketball. After he died, Timmy told his teammates he would never play again.

A guestbook message from October 2003 describes the boy as “not doing well…despite the counseling”— though a year later another friend writes that he and his mother are “doing as well as can be expected. Timmy is turning out to be a fine young man, and Evelyn is really holding things together for his sake.” She closes with the promise to Jack, “We will be there for your family as long as they need us.”

Evelyn Aron was born in the Philippines, and she and her husband had thought of retiring there to live on a salt farm they had purchased in 1997. The investment had given Jack a new nickname among his colleagues at Marsh & McLennan: “Jack Aron the Salt Baron.”

Jack Charles Aron worked in Information Technology for the multi-national insurance firm Marsh & McLennan Companies Inc. He was one of 295 Marsh employees (four of whom were Muslim) killed in World Trade Center Tower One on September 11, 2001. Raised in Washington Heights, New York City, Jack Aron was residing in the historic New Jersey town of Bergenfield at the time of his death. Bergenfield was also home to World Trade Centre victim Peter Negron, 34, who worked for the Port Authority of New York. His most glorious tribute: “dear mr.negon [sic], You were the funnyest and coolest father i ever knew. i wish you were still here to see all of us agian. all of peters freinds and peter ill never for get you. singned, kevin, glenn, mikey, david, and your son pete”

Bergenfield was also home to World Trade Centre victim Peter Negron, 34, who worked for the Port Authority of New York. His most glorious tribute: “dear mr.negon [sic], You were the funnyest and coolest father i ever knew. i wish you were still here to see all of us agian. all of peters freinds and peter ill never for get you. singned, kevin, glenn, mikey, david, and your son pete”

And Bergenfield is still the home of Col. John O’Do wd, 30-year army veteran.

wd, 30-year army veteran.

As commander of the New York District of the Army Corps of Engineers, O’Dowd was six blocks from the WTC when it was attacked. In 2002 he volunteered for service in Afghanistan as commander of the Afghan Engineering District. But this was only after a full year’s service as the officer in charge of transporting and sifting a seven-story pile of WTC debris— 1.3 million tons— to retrieve human remains and personal effects such as identification cards, and wedding bands.

We cannot know for sure, but perhaps Col. O’Dowd performed that service for his Bergenfield neighbor, Jack Charles Aron.

Cities and towns of every size, all over a world touched by war, have erected monuments upon which are etched the names of the fallen. The purpose of this has always been to remind anyone who sees them that deaths in battle happen to real, identifiable people, not to faceless masses. But the truth is that over time most of those etched names evolve into little more than decorative markings at which the eyes of witnesses glaze over.

Our era of mass communication permits us to keep a longer and more vivid hold on the individual identities of our war-dead, both military and civilian, through projects like 2996, and a great variety of other memorial acts. Three contributors to the internet guestbooks I’ve quoted here had the honor of “meeting” and remembering Jack Charles Aron long before I did.

At the one-year anniversary of 9/11, thousands of flags bearing the victims’ names were distributed to schools, and Tricia Schrum of Virginia carried Jack Aron with her that day. On the same day Rachel Putnam of Texas received and wore a wristband with his name. And that evening, Damon Corrigan of Washington State was proud to wear a tag bearing Jack Aron’s name as he participated in a performance of the “Rolling Requiem”, in which choirs and orchestras around the world performed Mozart’s haunting funeral Mass. No doubt there have been many others paying similar homage. The writers of the 2996 Project are just the latest.

Over these five years there’s been a sort of reflex to paint the title “hero” across the massed names of September 11 victims. But the friends of these victims, one by one, can think of other words. Jack Aron’s friends prefer: “sincere, honest, decent, good, remarkable, one-of-a-kind, a true gentleman, a mensch.” Jack Charles Aron - 1949-2001

Jack Charles Aron - 1949-2001

The antithesis of those that caused his death.

May he rest in peace.

Winefred's Well also pays tribute to the 26 Canadian victims of the September 11 attacks, with special remembrance of the families of Ken Basnicki-- Maureen, Erica, and Brennan, -- and of David Barkway -- Cindy, Jamie, and David.

to the 26 Canadian victims of the September 11 attacks, with special remembrance of the families of Ken Basnicki-- Maureen, Erica, and Brennan, -- and of David Barkway -- Cindy, Jamie, and David.

Enormous credit and thanks to the Dale Challoner Roe of the 2996 Tribute. Visit the site to read more tributes.

Photo credits:

1- tower collapse - United States Search and Rescue Task Force site

2 - missing - Bronston Jones - NYU Medical Centre wall

3 - night rescue - Joel Meyerowitz

4 - Cooper's pond, Bergenfield - Tom Schopper

5 - debris pile - Aris Economopoulos

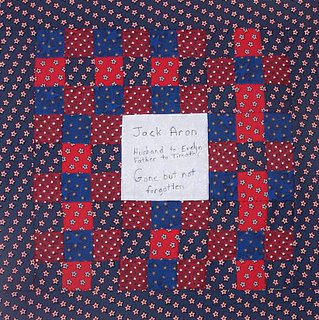

6 - quilt - United In Memory Gallery

7 - ashes - [previous post] - James Nachtwey

An outstanding gallery -- "Seeing the Horror" -- Digital Journalist/American Photo